Unlocking the Locks

by Chris Couch

March 2017 • North West Yachting

Okay, show of hands. Who doesn’t have at least a small pang of anxiety when thinking about going through the locks?

I will admit that after 27 years of dealing with the Ballard Locks, even I get anxious.

However, as a delivery captain, my anxiety is rooted in how long the transit will take. I often pre-position a boat outside the day before my expected departure just to avoid any delays. My record for waiting to navigate the locks is four hours. From those of us who transit for a living to the beginner who has yet to be indoctrinated, there are three things that will make the process smoother and ease some of that anxiety: preparation, preparation, and preparation. As in everything we do, preparation is the key to success. First, a little context.

The Evolution of the Lock

The first known locks were used in China during the Song Dynasty (960 to 1279) A.D. They appeared in Europe in the Netherlands in 1373. Completed in 1825, the 83-boat locks of the Erie Canal were the first pound locks built in the United States. Rising 568 feet from the Hudson River and traversing 363 miles, the Erie Canal today is still an amazing piece of engineering. Along with the Great Lakes, the Mississippi River, and the Intercoastal Waterway, it is part of a system of waterways called “The Great Loop” that enables boaters to circumnavigate the eastern half of the United States. It is the locks that enable these varied waterways to be connected.

Locks allow vessels of all kinds, private and commercial, to navigate from ocean to ocean and lake to lake. They allow vessels to transit up and down rivers and from one river to the next. Whether it is the Panama Canal, the scenic canals and rivers of Europe, the Columbia River, or our own Ballard Locks, the engine that drives all locks is gravity.

Gravity Power

Let’s take the Panama Canal as an example. Completed in 1914 to allow shipping to traverse the 50-mile Isthmus of Panama, the canal itself is 29 miles from one set of locks on the Caribbean side to the other set on the Pacific side. A set of three locks takes the skipper up to Gatun Lake and a set of three locks takes you back down. Gatun Lake is a man-made reservoir created from the damming of the Chagres River. When it was completed, it was the largest man-made reservoir in the world. This reservoir sits 87 feet above sea level and comprises most of the canal. When crossing the lake, the islands that you see while transiting the navigable channel are the tops of hills that make up the foothills leading up to the continental divide. The most famous part of the Panama Canal is the passage cutting through the mountains of the divide, which comprises only about a mile of the entire passage.

The elevated Gatun Lake is the engine that drives the entire operation. Its water flows into the locks, raising ships up lock by lock, and then letting them back down. You can imagine the amount of water used to run two sets of six locks, each 110 feet by 1,050 feet. Now add the newly expanded locks at 160 feet by 1,200 feet and you can imagine the job of managing the water supply. In December of 2015, I transited the Panama Canal for my fifth time. The level of Gatun Lake was a full two feet lower than where it was supposed to be for that time of year. This directly affects the draft of the vessels transiting Gatun Lake. It was August of 2014 that the Canal Authority announced that cargo weight limits may have to be imposed. Shifting climate patterns have caused the wet season to become drier than historical norms, bad news at a time when the canal is expanding its operations.

The Ballard Locks

Just as with the Panama Canal, our own Ballard Locks depends on a large source of water to operate. In the early days of the Pacific Northwest, coal and timber were two of the pillars of our economy. Driven by the need to move coal and timber from the Lake Washington area to Puget Sound as early as 1854, discussion had started about linking the two bodies of water. In 1867 the U.S. Navy pushed that idea along with their desire for a freshwater base and shipyard. The U.S. Army Corp of Engineers would start the planning in 1891 and the funding wouldn’t be secured from Congress until 1902. It was in 1910 when Major Hiram M. Chittenden was given command of the area’s Army Corps of Engineers that the project finally took shape and started in earnest.

The Hiram M. Chittenden Locks, or Ballard Locks as they are more commonly known, were completed in 1917. They were part of a larger Lake Washington Ship Canal project to connect Lake Washington, Lake Union, and Salmon Bay to Puget Sound. This larger project was officially completed in 1934. It is interesting to note that with the opening of the Ship Canal and Locks in 1917, the water level of Lake Washington was lowered almost nine feet. In addition to exposing a lot of new shoreline, it had the effect of reversing the flow of the Black River in Renton. The Black River flowed south from the south end of the lake and, joined by the Carbon River, joined the Duwamish River in Tukwila. Today the Black River does not exist and the Carbon River now flows north into Lake Washington. The Black River to the Duwamish River and then to Elliott Bay was just one of four other routes that were considered as the major Lake Washington to Puget Sound waterway. These other routes were eventually eliminated from contention as either too long or too difficult to construct.

How to Unlock the Ballard Locks

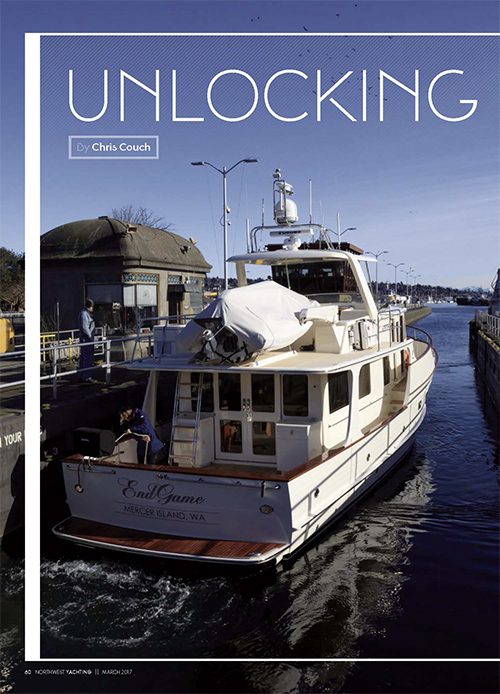

LowerLockNow that we’ve gotten the historical context out of the way, we can focus on how to get you and your boat through the Ballard Locks. The Ballard Locks consist of two separate locks: a small lock and a large lock. The small lock is 150 feet long by 30 feet wide and is used for vessels approximately 100 feet and smaller. I routinely transit with a 100-foot motoryacht that occupies the entire chamber. The large lock has two separate chambers and when used together is up to 825 feet long by 80 feet wide. The elevation of the lake varies between 20 to 22 feet above sea level. The lowest level occurs during the winter and the highest near the beginning of the summer. The level is high during the summer months to store water in case we have a dry season. There is a dam and spillway next to the locks that regulates the water level and a salmon ladder on the south side of the complex.

For both the big and small locks, when transiting westbound, i.e. from the lake to the Sound, the typical side you will tie up on is your starboard side. When transiting eastbound, or from the Sound to the lake, you will be on your port side most of the time. This is not always the case however, so being prepared for both sides is highly recommended. I cannot stress this enough. Being prepared for the big or small lock and for port or starboard side is very important. You must be prepared for any situation and any contingency.

Preparation for the locks should start taking place well before you arrive. I always start with the fenders. For both the big and small locks, your vessel will be up against either a concrete or steel wall. Fenders should be placed to protect the widest parts of your vessel. I recommend at least three on each side and the largest you have. Most vessels I see are using fenders that should be much bigger. Remember what fenders do. Fenders are there to protect your vessel. The bigger, the better.

Next comes the lines. The sides of the small lock chamber are lined with a floating sleeve. It is this sleeve that you will tie up to. You will need a bow and a stern line. The eyes of the lines are attached to the cleats on your boat. When you move into position on the sleeve, the line will run from the boat, around a bollard on the top of the sleeve, and back to the boat. The sleeve is designed to slide up and down the wall of the chamber with the water level. Once your lines are secured, there is nothing else to do. The lock attendant will tell you which bollard to use and will probably assist as well. Remember, for the small lock, the eye of the line is attached to the bow and stern cleat.

For the large lock, it is opposite. Your vessel is tied up to the side of the chamber. You will need two lines that are at least 50 feet in length. The lock attendants will be there to catch your bow and stern lines and it is the eyes of the lines that you hand them. They then place the eyes of the lines on a bollard on the wall and you will secure the lines to your bow and stern cleats. As the water level changes, you will either let out line or take it in. You want to keep the slack out of the line, but not too tight. The goal is to keep your position fore and aft on the wall, but not too tight against it. You may also have to re-adjust your fenders as you go up or down.

Transiting westbound from the lake to the Sound is the easier of the two directions. You are at the top of the locks and the attendants are right there to readily take your lines. Going eastbound or from the Sound to the lake is a bit more challenging because you are at the bottom of the chambers. In the small locks, you have to get the lines around the bollards yourself. In the large lock, the lock attendant will throw you a heaving line which you will tie to the eye of your line. He will pull your line up. Important: Ensure that the other end is tied off to something so that you don’t lose it.

I highly recommend that you set up and prepare for both the small and large lock and prepare for port or starboard side. The lock that is being used depends on the volume and size of the traffic. Commercial vessels always take priority over private vessels. The locks are usually short-handed, so they will only have enough personnel to man one lock at a time. The lock being used commonly switches from one to the other and then back again, so being prepared for both is very important.

Once you have arrived at the locks, there are traffic-style red and green lights positioned at either end of the large and small locks. These will indicate when you should proceed into the lock. With the small lock it is first come, first serve. With the large lock it is larger vessels first. These rules are important if you don’t want to incur the wrath of other boaters or the locks attendants. The attendants will put the larger vessels on the wall first. Smaller vessels will then be rafted up next to the larger vessels. Have your fenders and lines prepared for this. It is highly likely that you will have vessels on the other side of you, and this is yet another reason for having fenders on both sides.

Be courteous of others while you wait in line and stay clear of departing traffic. Listen for any announcements by the Army Corp of Engineers on their public address system and listen to the lock attendants once you start your approach. Above all, be prepared. Just with our wonderful Seattle area traffic, there are good times and bad times to commute through the Ballard Locks. No matter what time of the year, there are some general times that give you a better chance at getting through without much delay. Fridays for heading west (outbound) and Sunday afternoons for heading east (inbound) are generally busy. Just as with rush hour, the earlier in the day, the better to avoid the crowds. When heading outbound, I will shoot for very early in the morning no matter what the day. Coming back, I will pretty much avoid Sunday afternoon altogether. I have been known to overnight at Shilshole Bay Marina and fi nish the trip Monday morning, especially during the summer. Holidays year-round can be especially busy: New Years, Fourth of July, Seafair, etc. Planning ahead and transiting the locks during the off times can make a really big difference. It’s also worth noting that, due to the federal funding freeze of the current administration and congress, there will be fewer lock attendants on hand in the coming months. This development bodes ill for the crowded summer days ahead.

Captain Chris Couch is a successful Pacific Northwest-based delivery captain who has been widely used by companies like Alexander Marine for the last 26 years. Couch enjoyed a 14-year career in the U.S. Coast Guard that took him around the country to the East Coast, Gulf, and West Coast on all kinds of vessels. He has been at the helm through the Panama Canal five times and for four transpacific crossings. His book, The Checklist, is enjoyed by and distributed to yachts owners and is a fantastic resource that covers just about everything relevant to a PNW Boater. You can buy The Checklist, check out his other publications, or contact him at compassheadings.com.

NWY